Catalogue Note:

“When all the people of the world know beauty as beauty, this is no longer beauty but ugliness. When they all know the good as good, this is no longer good but evil. Therefore: Being and non-being produce each other; Difficult and easy complete each other; Long and short contrast with each other; High and low distinguish each other; Sound and voice harmonize with each other; Front and behind accompany each other. Therefore the sage manages affairs without action, and spreads doctrines without words. All things arise, and he does not turn away from them. He produces them but does not take possession of them. He acts but does not rely on his own ability. He accomplishes his task but does not claim credit for it. It is precisely because he does not claim credit that his accomplishment remains with him.” (Laozi, “Dao De Jing”, Chapter 2)

T’ang Haywen once commented that “In the search for beauty, there is a danger of falling into the fatal trap of being entranced by external appearance; the result is inevitably a piece of art that has no real power. On the other hand, if you try to root out beauty at all costs, then you may fall into the opposite trap of ugliness.” (“T’ang Haywen,” Goethe Art Center, Taichung, 1998, p. 5). This remark displays a striking correspondence with the first lines of Chapter 2 of the “Dao De Jing”: “When all the people of the world know beauty as beauty, this is no longer beauty but ugliness.” What T’ang Haywen strove for in his art was not simply to make “beauty” appear on the canvas. He believed that the creation of art had to operate through the unconscious mind, and that the artist needed to possess an in-depth understanding of their own self, in order for the completed painting to qualify as an art work. Only if the artist was sufficiently self-aware could they hope to produce a complete, mature artwork; as T’ang saw it, the apogee of artistic creation lay in selfreflection and spiritual enlightenment.

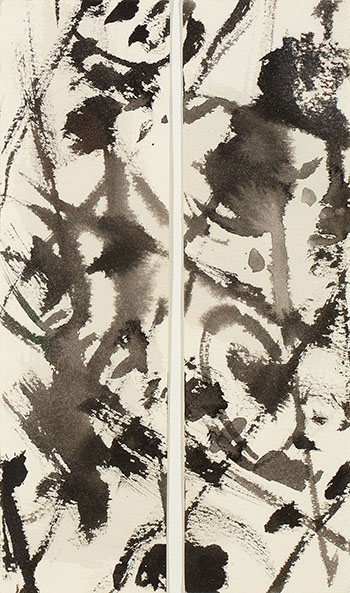

In the art of T’ang Haywen, the use of composition that reveals the rhythms of traditional Chinese calligraphy reflects not only T’ang’s familiarity with Taoist philosophy, but also T’ang’s overall cosmological viewpoint. Taking a sheet of blank paper and creating another world on it – this is how T’ang saw the realization of artistic creation, as an expression of the artist’s inner world, with the paper or canvas being transformed into a medium that carries the artist’s cultivation. T’ang Haywen did not feel that his conversion to Catholicism in any way conflicted with his traditional beliefs; one might go so far as to say that T’ang took a distinctively Chinese philosophy of painting and combined it with Western techniques and forms of expression; his fusion of two cultures in himself enabled him to reach a pinnacle of self-realization. T’ang himself felt that the conceptual framework of “one dividing into two, and two merging into one” could provide a space for innovation, and that this approach fits well with how the world actually operates (“T’ang Haywen,” Goethe Art Center, Taichung, 1998, p. 5). In his art, T’ang Haywen had to achieve a fusion of Chinese and Western; through the “enlightenment” that T’ang achieved, these seemingly diametrically opposed elements combined to become a source of wisdom, and helped to forge T’ang’s unique artistic lexicon. At the spiritual level, the smooth, flowing brushstrokes of traditional Chinese ink-brush painting spread out in the space formed by the painting’s composition to create a new universe. The artist follows the dictates of his heart, refraining from any unnecessary interference intended to “perfect” the work, and adhering to the tenets of the “Dao De Jing”: “Therefore the sage manages affairs without action, and spreads doctrines without words. All things arise, and he does not turn away from them. He produces them but does not take possession of them. He acts but does not rely on his own ability. He accomplishes his task but does not claim credit for it. It is precisely because he does not claim credit that his accomplishment remains with him.” By “managing affairs without action” and “spreading doctrine without words,” things will grow and develop naturally of their own accord. This is the path along which T’ang’s art evolved.

In T’ang Haywen’s later work, the influence of the philosophy of traditional Chinese ink-brush painting – which emphasizes the effective use of blank space on the canvas – is very apparent; the abstract representation used in these later paintings can be seen as reflecting the influence of Western abstract art, which had become the mainstream in the Western artistic school by this time. And yet T’ang Haywen was never one to just blindly follow trends. He respected his own inner wisdom, and stuck resolutely to his course; in his art, he remained committed to the goal that had inspired him from the beginning – the search for “beauty” – while also continuing to explore the essence of his own inner nature. The knowledge that T’ang had acquired about life took permanent form in the diptych works that he produced, in which “one divides into two, and two merge into one.”

T’ang Haywen once commented that “In the search for beauty, there is a danger of falling into the fatal trap of being entranced by external appearance; the result is inevitably a piece of art that has no real power. On the other hand, if you try to root out beauty at all costs, then you may fall into the opposite trap of ugliness.” (“T’ang Haywen,” Goethe Art Center, Taichung, 1998, p. 5). This remark displays a striking correspondence with the first lines of Chapter 2 of the “Dao De Jing”: “When all the people of the world know beauty as beauty, this is no longer beauty but ugliness.” What T’ang Haywen strove for in his art was not simply to make “beauty” appear on the canvas. He believed that the creation of art had to operate through the unconscious mind, and that the artist needed to possess an in-depth understanding of their own self, in order for the completed painting to qualify as an art work. Only if the artist was sufficiently self-aware could they hope to produce a complete, mature artwork; as T’ang saw it, the apogee of artistic creation lay in selfreflection and spiritual enlightenment.

In the art of T’ang Haywen, the use of composition that reveals the rhythms of traditional Chinese calligraphy reflects not only T’ang’s familiarity with Taoist philosophy, but also T’ang’s overall cosmological viewpoint. Taking a sheet of blank paper and creating another world on it – this is how T’ang saw the realization of artistic creation, as an expression of the artist’s inner world, with the paper or canvas being transformed into a medium that carries the artist’s cultivation. T’ang Haywen did not feel that his conversion to Catholicism in any way conflicted with his traditional beliefs; one might go so far as to say that T’ang took a distinctively Chinese philosophy of painting and combined it with Western techniques and forms of expression; his fusion of two cultures in himself enabled him to reach a pinnacle of self-realization. T’ang himself felt that the conceptual framework of “one dividing into two, and two merging into one” could provide a space for innovation, and that this approach fits well with how the world actually operates (“T’ang Haywen,” Goethe Art Center, Taichung, 1998, p. 5). In his art, T’ang Haywen had to achieve a fusion of Chinese and Western; through the “enlightenment” that T’ang achieved, these seemingly diametrically opposed elements combined to become a source of wisdom, and helped to forge T’ang’s unique artistic lexicon. At the spiritual level, the smooth, flowing brushstrokes of traditional Chinese ink-brush painting spread out in the space formed by the painting’s composition to create a new universe. The artist follows the dictates of his heart, refraining from any unnecessary interference intended to “perfect” the work, and adhering to the tenets of the “Dao De Jing”: “Therefore the sage manages affairs without action, and spreads doctrines without words. All things arise, and he does not turn away from them. He produces them but does not take possession of them. He acts but does not rely on his own ability. He accomplishes his task but does not claim credit for it. It is precisely because he does not claim credit that his accomplishment remains with him.” By “managing affairs without action” and “spreading doctrine without words,” things will grow and develop naturally of their own accord. This is the path along which T’ang’s art evolved.

In T’ang Haywen’s later work, the influence of the philosophy of traditional Chinese ink-brush painting – which emphasizes the effective use of blank space on the canvas – is very apparent; the abstract representation used in these later paintings can be seen as reflecting the influence of Western abstract art, which had become the mainstream in the Western artistic school by this time. And yet T’ang Haywen was never one to just blindly follow trends. He respected his own inner wisdom, and stuck resolutely to his course; in his art, he remained committed to the goal that had inspired him from the beginning – the search for “beauty” – while also continuing to explore the essence of his own inner nature. The knowledge that T’ang had acquired about life took permanent form in the diptych works that he produced, in which “one divides into two, and two merge into one.”