EXHIBITED:

1971–2010 Forty Years Retrospective Review of Zhou Chunya, Shanghai Art Museum, Shanghai, June 13–23, 2010

ILLUSTRATED:

Zhou Chunya, Timezone 8, Hong Kong, 2010, color illustrated, pp. 432–433

Catalogue Note:

In examining the artistic movements and stylistic developments of Chinese artists over the past few decades, Zhou Chunya stands apart from his contemporaries. In inspiration, symbolism, technique, and purpose, Zhou has effectively developed his own artistic direction, continually diverging from the movements around him to explore and establish his own means of expression through art. Rejecting participation in the politically and ideologically charged artistic theories celebrated by other contemporary artists in China, Zhou instead cultivated his own passions and interests through the establishment of several iconic series: "Tibet", "Stones", "Flowers", "Peach Blossoms", and "Green Dog". Zhou’s unique and distinctive voice has earned him recognition throughout his career, culminating in his first retrospective held at the Shanghai Art Museum in 2010. The same year, Zhou was named Artist of the Year at the 2010 Art Power Awards, a title awarded the previous year to his close friend, Zhang Xiaogang. Zhou’s refusal to mold his artistic voice to a discernable movement has set his work apart in both originality of style and expression.

Zhou’s first departure from the artistic movements around him came in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. While Zhou’s classmates at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute united to express the social upheaval and historical trauma of the Cultural Revolution through the newly established Scar Art movement, Zhou elected instead to focus on depictions of the idyllic, agrarian lives of the Tibetan people. Zhou explains that while he appreciated the Scar Art narratives of his peers, his artistic interests lay elsewhere, stating, “I only wanted to sketch from life because in so doing I was confronting an immediate, living nature. This allowed my artistic expression to remain at one with my passions.” Zhou’s Tibetan studies do not represent politicized metaphors or social theories, but instead focus on the simple aesthetic inspiration that Zhou found in the colors and rustic beauty of both the people and landscape.

Following his time in Tibet, Zhou left a socially tumultuous China to obtain his master’s degree at the Gesamthochschule in Kassel, Germany. Of his time in Germany, Zhou claims “the classroom where I really studied was the art museums and galleries of Germany and other European countries.” Exposure to Western artistic movements such as Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism, and the Neo–Expressionist “Junge Wilde” (Wild Youth) theory expanded Zhou’s aesthetic and stylistically influenced his artistic exploration.

Despite Zhou’s identification with the artistic movements he discovered in Germany, he did not remain there long, returning to China in 1989. China has always held certain sway over Zhou, who states simply, “I have been deeply influenced by Chinese tradition, which I can never be rid of wherever I am.” It was in pursuit of this Chinese tradition that Zhou developed both his Stone and Flower series, combining the visual experimentation of the Western modern movements he had discovered in Germany with the traditional elements of Chinese literati painters. While his contemporaries in China were participating in the New Wave, Cynical Realism, and Political Pop movements saturated with social and political commentary, Zhou chose subject matter quintessential to the literati aesthetic, devoid of the contentious activism inherent in the movements around him.

While unmistakably influenced by traditional literati painters such as Dong Qichang, Shi Tao, Bada Shanren, and Huang Binhong, Zhou’s exploration of traditional themes sought to expand upon existing conventions by incorporating the brash colors and influences of Western artistic movements. Zhou admits, “I liked the forms…of the literati, but wasn’t satisfied with that overly moderate, introspective character, so I thought up a bold and risky experiment—to use that elegant form to convey violent, even erotic overtones.” With such an experiment in mind, both the "Stone" and "Flower" series demonstrate Zhou’s aesthetic exploration, imbuing the grace and fluidity of the literati tradition with the power and passion of modern artistic movements. In his Peach Blossom series, Zhou utilizes a subject already replete with significance from mythology and lore, augmenting the inherent symbolism of the "peach blossom" in his paintings through his striking utilization of color and effect. Zhou describes his peach blossoms as, “in a fluid emotion and mood of colors, flows indulgence of primitive and sincere imaginations. It is the total release of human nature against a grand scene, an explosion of gentle violence.” A reoccurring motif in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean art, peach blossoms impart connotations of immortality, femininity, fragility, and sensuality. This blending of erotic, modern overtones with traditional compositional elements and themes has become a key characterization for much of Zhou’s work.

Zhou Chunya’s "Stone" series specifically addresses this convergence of aesthetic traditions. Addressing this series, Zhou explains:

When I created these ‘stones,’ I had been studying the landscape paintings of the literati. I didn’t, however, perceive them in a way like the Chinese traditional painters. I did not attempt to scrutinize their material properties and patterns and shapes, but to search, according to my own purposes of expression, for those features that all together estrange and amaze me. I have spent much time studying texture, as I tried compulsively to capture and ponder over the deep–rooted factors that affect our visual perception of the stones. Their augmentation and magnification are in essence the form; their visualization is in essence the content, so they require no further explanation or reference. These stones are more astounding and startling than those that are viewed and interpreted from a conceptual and technical perspective.

With each construction, Zhou seeks to utilize the framework established by literati compositions and build upon this foundation with western Expressionist stylistic elements. Often erotic or sensual, Zhou imbues each Stone configuration with an emotional core, animating each static pillar. With particular attention to the multifaceted surfaces of each stone, Zhou layers colors and stark contrasts to emphasize the sense of dimension and volume for each piece.

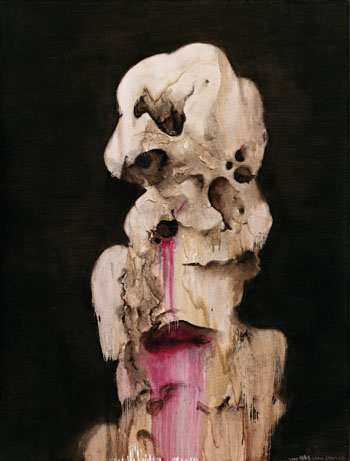

"Taihu Lake Stone" presents an arresting example of Zhou’s "Stone" series. Standing starkly against a commanding black background, the stone rises upward in a pitted, textural column. With special attention to the surface and details of each carved and hollowed cavity, Zhou has rendered the static stone with the character and animus of a living organism. With the startling red which pours from the gaping, black openings, this stone arrests attention, and radiates a sense of deeper visceral emotion. The stones from Taihu Lake have provided a particular source of inspiration for the artist, who views their structural composition as ideal for the expression of both traditional and expressionist ideals. Expounding on this fascination, Zhou states:

The stone has been an unfailing subject in traditional Chinese art. Its staunch solidity and its texture provide the artist a perfect medium to present their spirit and technical method. Stones from the Taihu Lake in particular are even more affluent and complicated. The smooth contour demonstrates an artificial, implicit, and flinty feel, with which an artist could produce a complete image without any beautification…I didn’t think too much about it, yet once when I was lecturing at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, a student pointed out that my Taihu Stone series appeared to be bloody and violent. At that moment I realized the charisma of Taihu Stones, as well as its contradictory nature.

The current lot “Taihu Lake Stone” demonstrates this violent, passionate nature to which Zhou refers. High contrast and a meticulous attention to subtlety and detail enliven the stone, establishing an arresting composition rife with sensational vibrancy. However, Zhou’s "Taihu Lake Stone" works are the most mature series among Stone, as the form itself is close to perfect, Zhou found it is un–necessary to develop further, and that’s the reason why he created "Taihu Lake Stone" only from 1999 to 2000. With the tremendous size and rarity, this painting is an exceptionally desirable work of art.

Throughout his artistic career, Zhou has continually sought to explore his own originality, refusing participation in surrounding trends and movements to instead pursue his own unique representation of aesthetic inspiration. As he continually extends his artistic investigation, he seeks persistently to represent truth. In his own words, Zhou Chunya insists, “True ideas are very important. What is true is more important than what is correct.”